Counter-UAS in the United States: Authority, Environment, and the Limits of Technology

By: Kevin Padilla.

Counter-UAS in the United States: Why Technology Alone Is Not the Answer

Uncrewed Aircraft Systems have begun to alter the security landscape in the United States, though understanding has not kept pace with adoption. Drones are no longer experimental or niche, but their integration into public safety, infrastructure, and commercial operations remains uneven and often poorly understood. Enough adoption has occurred for decision-makers to recognize that drones can create risk, yet not enough clarity exists around how, when, or why that risk manifests.

That gap matters. The same commercially available platforms enabling legitimate operations are equally accessible to criminal, disruptive, or hostile actors. As a result, organizations often sense the problem before they understand it, recognizing drones as a potential issue without having the frameworks needed to assess intent, authority, or response options.

The Misconception of Counter-UAS as a “Device”

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

A persistent misconception in counter-drone planning is the belief that CUAS is solved by acquiring the right sensor, jammer, or defeat mechanism. In practice, detection alone does not produce security outcomes. Nor does the mere presence of a mitigation capability, particularly when most organizations lack the legal authority to use it.

In the U.S. domestic environment, counter-UAS must be understood as a coordinated set of processes rather than a standalone device. Detection, identification, assessment, decision-making, and response must be aligned with legal authority, operating environment, and organizational roles. When any one of these elements is missing or misaligned, the system fails regardless of technical sophistication.

Most domestic organizations operate under a protective posture by default. Federal law centralizes authority over airspace and spectrum, and only a narrow set of federal entities are authorized to conduct active interdiction. For state, local, tribal, and private operators, lawful counter-UAS activity typically centers on early detection, contextual assessment, documentation, coordination, and escalation. Systems designed around unrestricted takedown authority are often operationally unusable in real U.S. environments.

The Dual-Use Drone Problem

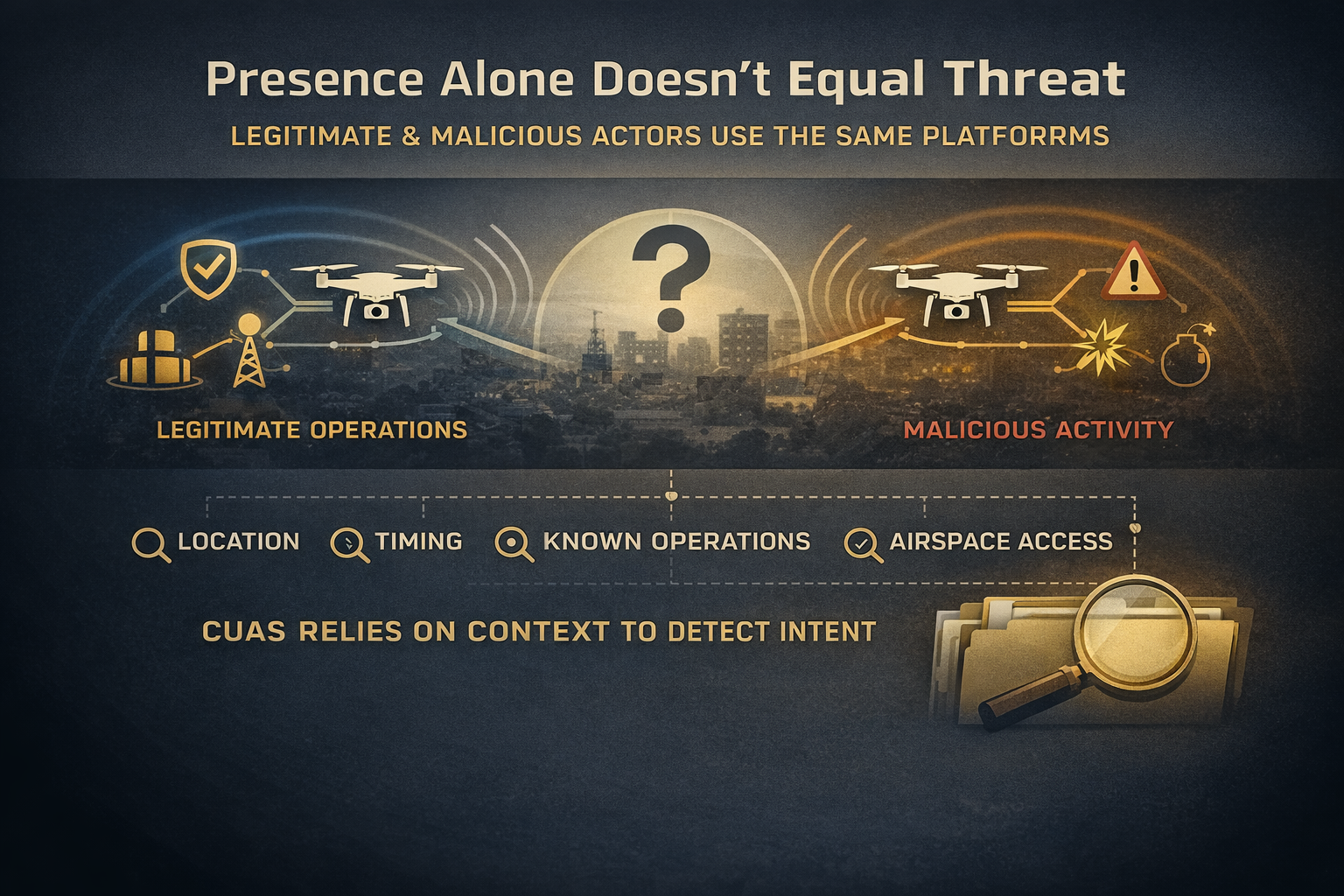

What makes the U.S. counter-UAS problem uniquely difficult is the convergence of capability between legitimate and malicious users. The same airframes, radios, sensors, and software support infrastructure inspection one day and hostile surveillance the next. Flight behavior, altitude, loitering, and proximity to assets are unreliable indicators of intent because they overlap directly with normal commercial and public safety operations.

Most CUAS technologies detect presence, not purpose. Intent must be inferred from context. Location, timing, behavior relative to protected assets, correlation with known operations, and alignment with airspace authorizations matter more than any single sensor input. Without that context, systems generate false positives that disrupt compliant missions or false negatives that allow adversaries to probe undetected.

The consequence is not merely operational friction. False alerts erode trust in CUAS outputs, desensitize operators, and delay response when a genuine threat emerges. Over time, teams learn to ignore systems that cannot reliably distinguish signal from noise.

Adversary Adaptation Favors Speed, Not Strength

Another structural challenge in domestic counter-UAS is the mismatch between adversary adaptation cycles and defensive timelines. Malicious actors benefit from a commercial technology ecosystem that evolves rapidly and globally. Firmware updates, autonomy features, and payload integrations are released on consumer timelines, not security timelines.

Experimentation with drones is cheap, low-risk, and often anonymous. Failed attempts rarely result in attribution or consequence, incentivizing trial-and-error learning. Defensive systems, by contrast, operate under procurement, certification, legal review, and governance constraints. Even when new capabilities exist, they are slow to field and slower to integrate.

This asymmetry means counter-UAS systems optimized around static threat models will age poorly. The most resilient architectures prioritize modularity, adaptability, and procedural resilience rather than optimization for fixed signatures or tactics.

When Drones Are Also the Asset

A defining feature of U.S. counter-UAS operations is that drones are not just threats. They are increasingly mission-critical assets. Public safety agencies, utilities, event security teams, and infrastructure operators rely on UAS for situational awareness, inspection, and response. Disrupting legitimate drone operations can degrade safety, slow response, and introduce new risks.

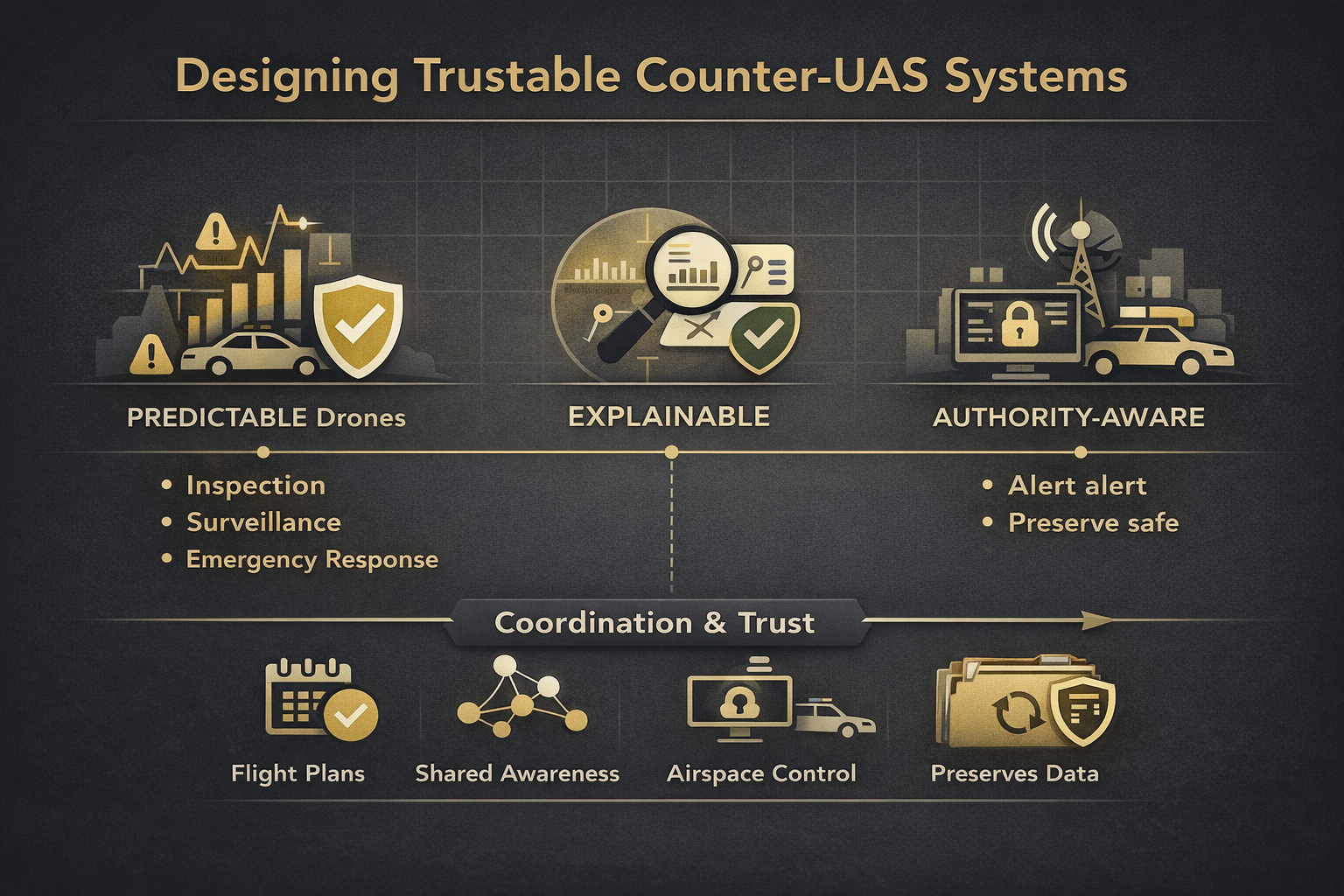

This creates a deconfliction problem that is frequently underestimated. Detection systems without awareness of authorized flights generate unnecessary alerts. Poorly governed mitigation risks interfering with friendly aircraft. Effective counter-UAS therefore depends as much on procedural coordination as on technology. Advance notification, airspace coordination, shared situational awareness, and clear operating boundaries are essential.

Trust becomes central. In domestic contexts, most counter-drone actions are indirect. Detection often leads to movement, schedule changes, buffer creation, or escalation rather than immediate engagement. If operators do not trust the system’s accuracy, explainability, or authority awareness, they will hesitate or ignore it entirely.

Authority Shapes Everything

Unlike overseas or military environments, domestic counter-UAS is defined by legal boundaries. Property ownership does not confer control of airspace. Lawful drone overflight is generally permitted when conducted in compliance with FAA regulations. Even when a drone is unwanted or suspicious, most organizations remain legally constrained to observation, documentation, and coordination.

This does not mean counter-UAS is passive. Early detection paired with credible assessment constrains adversary options. It compresses response timelines, forces behavior changes, and enables escalation to authorized partners. A drone that is detected, tracked, documented, and attributed is operating in a far less permissive environment than one that is unseen.

Authority is not uniform across environments. Temporary Flight Restrictions, Prohibited Areas, and the National Capital Region operate under denser authority frameworks where escalation thresholds are lower and coordination is preplanned. Counter-UAS systems must adapt their posture accordingly. Designs that assume one authority model will fail in others.

Why Attribution Often Matters More Than Interdiction

In the U.S. rule-of-law environment, attribution frequently delivers more long-term security value than immediate takedown. Stopping a single flight may prevent an incident, but without attribution the adversary learns and returns. Identifying launch locations, operators, and patterns enables investigation, prosecution, and deterrence.

Effective attribution requires evidentiary rigor. Data integrity, time synchronization, documentation of assessment rationale, and lawful collection methods are essential. Systems that defeat drones but discard evidence may solve the moment while undermining accountability.

This emphasis reshapes how success should be measured. Counter-UAS effectiveness is not how often a drone is neutralized, but whether adversarial activity results in consequence.

Designing Trustable Counter-UAS Systems

Trustable counter-UAS systems share several characteristics. They are predictable, with consistent alerting and clearly defined escalation logic. They are explainable, allowing operators to understand why an assessment was made and defend decisions under review. They are authority-aware, recommending only actions users are legally permitted to take. They integrate into existing security and operations workflows rather than competing with them. And they preserve data for after-action review, learning, and accountability.

Systems lacking these qualities may function technically, but they will not be acted upon under pressure.

The Strategic Takeaway

Domestic counter-UAS effectiveness is driven less by technology selection than by how capabilities are governed, integrated, and exercised. Most U.S. environments demand a protective posture focused on early warning, decision support, and option preservation. Projective capability is context-specific and authority-dependent.

Organizations that treat counter-UAS as a governed system of processes rather than a product are better positioned to manage ambiguity, coexist with legitimate drone operations, and reduce risk over time. As drone use continues to expand across civilian life, sustainable security will belong to those who align technology with authority, environment, and human decision-making rather than those who chase hardware alone.

Above. It. All.